We were very saddened to learn of the death in November last year of Professor Andrew Tallon, whose obituary was published on the Society of Architectural Historians’ website.

Although we did not have the privilege of meeting Prof. Tallon, we had corresponded with him about our shared interest in digital methods in relation to medieval architecture. Ongoing medical treatment meant that, although delighted to have been asked, he was unable to accept our invitation to speak at our 2016 conference. We had hoped to invite him again to speak at our next symposium, where he will now be a sad absence.

Prof. Tallon was one of the first medieval architectural historians to identify the potential of laser scanning to the study of medieval architecture and the value of digital tools both for research and outreach purposes. His contribution to the Mapping Gothic France project has helped to make it a hugely valuable resource and he explored the possibilities offered by film and exhibitions to share his knowledge of French Gothic.

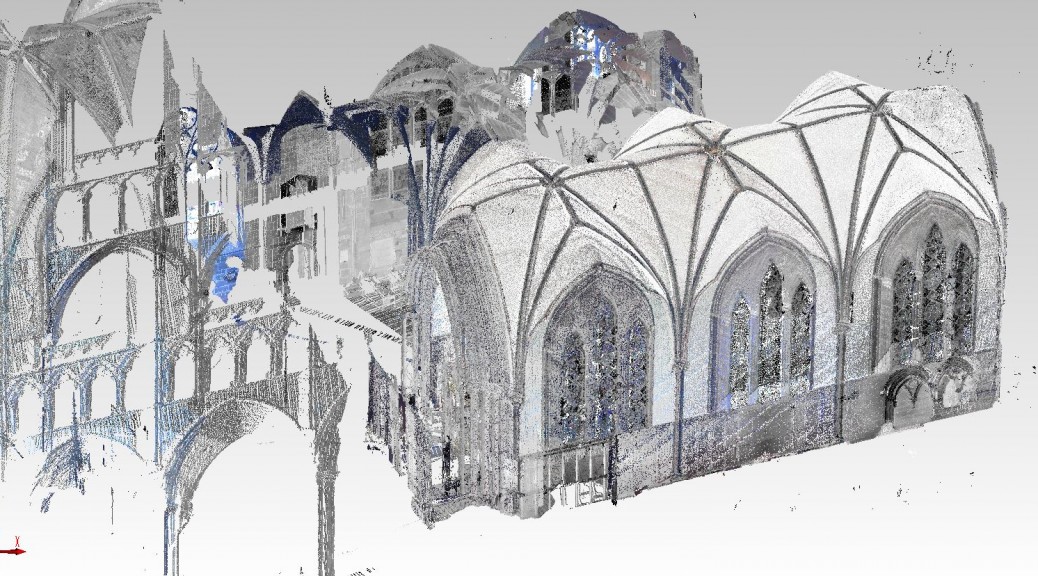

Of particular significance to our own research, Prof Tallon used the data gathered from laser scanning to look at medieval design methods, providing secure data to overcome the obstacles faced by earlier researchers. In his article ‘Divining Proportions in the Digital Age’ in Architectural Histories 2:1 (2014), he discussed the technique of laser scanning in relation to analysis of the planning of the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. Showing a generosity we understand to have been typical of his character, he also shared his data with Robert Bork, who used it in his article ‘The Geometry of Bourges Cathedral’, Architectural Histories, 2.1 (2014). Equally importantly, Prof Tallon used data derived from laser scanning to inform a method he described as ‘spatial archaeology’, the close observation of building deformation. In articles such as ‘Rethinking Medieval Structure’, in New Approaches to Medieval Architecture, ed. R. Bork, W.W. Clark and A. McGehee (Farnham and Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2011), pp.209-17, he used this approach to demonstrate convincingly that flying buttresses had been a feature of French Gothic architecture from the outset, rather than being added to early Gothic buildings at a later stage. Although the English Gothic buildings on which we are focussing are far less adventurous in engineering terms than French cathedrals, we have used his methods to argue that apparent anomalies within our data are unlikely to result from settlement, as the walls we have so far analysed are similarly vertical. Nor was Prof Tallon’s research confined to questions of construction: he was equally interested both in historiography and symbolism. His research on the supposed ‘refinements’ to Gothic proposed in the early twentieth century by William Goodyear (1846-1923), published as ‘An Architecture of Perfection’ in the JSAH, 72:4 (2013), pp.530-54 showed that not only were such displacements not intended by the original builders but also went against their understanding of the importance of being ‘upright’ in both structural and moral terms.

As Prof Tallon had undertaken a major programme of scanning at Bourges Cathedral, we had been looking forward to discussing with him any findings on the three-dimensionally curved ribs of the ambulatory, which seem to be unique for their date. It is a matter of great regret to us that his untimely death cut short an ongoing conversation and has deprived our field of one of its great innovators. He will be very sorely missed.